In Russian

In German

In Polish

Ivan Kurilla on Denis Karagodin who is investigating the death of his great grandfather.

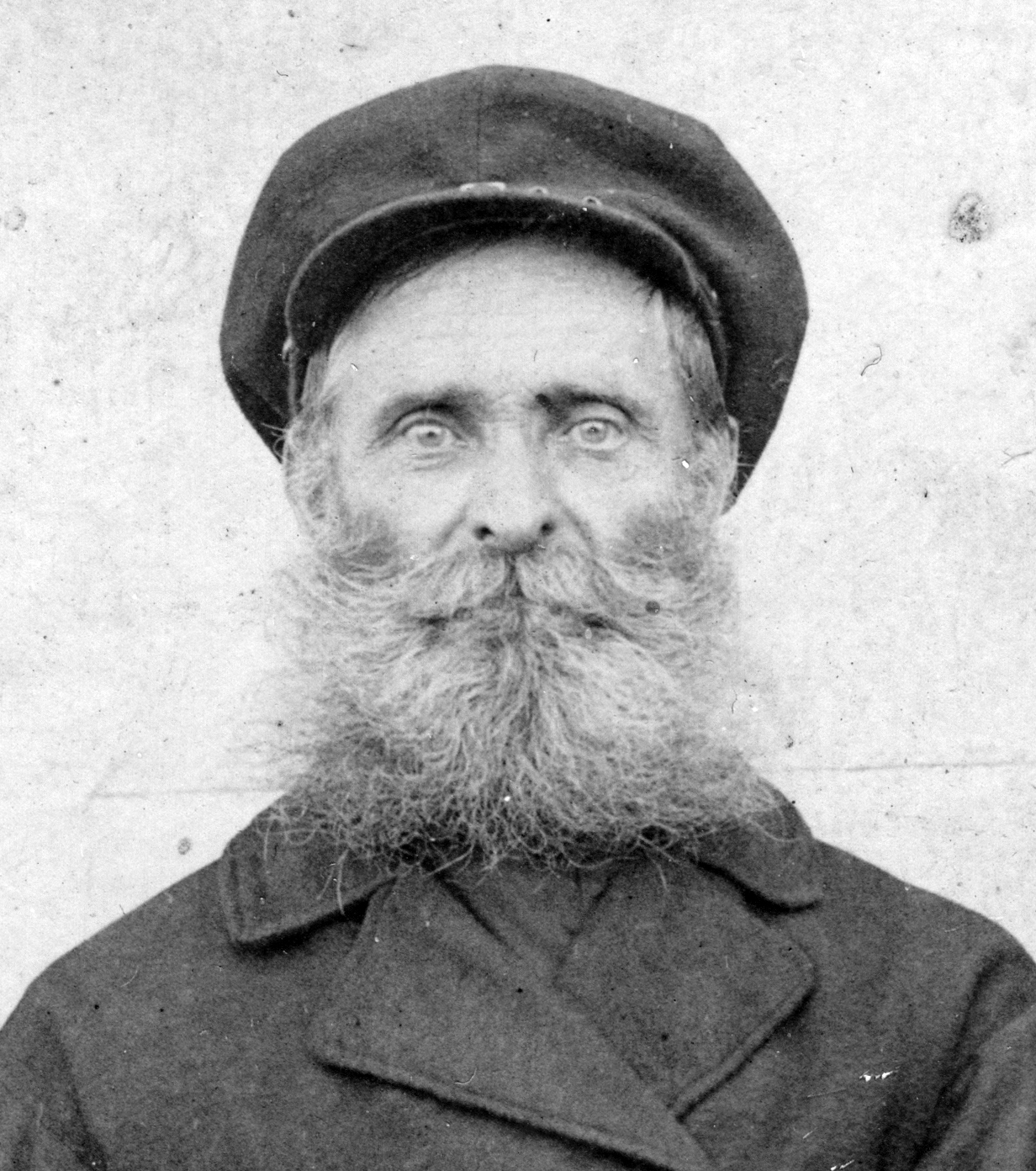

Stepan Karagodin was shot by the NKVD firing squad in early 1938 after he, among many other ‘Russian Harbinites’, was convicted as a ‘resident of the Japanese military intelligence’. Eighty years after his execution, Stepan Karagodin’s great grandson Denis demands that the FSB investigates the murder of his great grandfather and names the people responsible for this crime.

Ivan Kurilla – Russian historian, PhD, professor at the European University in St Petersburg.

The story of Denis Karagodin [Read in English], alumnus of the Tomsk State University who is investigating the murder of his great grandfather Stepan during the Great Purge in early 1938, has gone viral overnight. Stepan Karagordin was shot by an NKVD firing squad (NKVD is the Russian abbreviation for the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) after he was convicted as a ‘resident of the Japanese military intelligence’ together with a group of ‘Russian Harbinites’. Denis demands that the FSB, the main successor agency to the Soviet KGB and NKVD, investigate the murder of his great grandfather and name those responsible for this crime. In Russia, such a step is both logical and impossible at the same time.

GENERATION OF THE UNWHIPPED

Millions of Soviet citizens lost relatives during the time of Great Purges, received incomplete information about their deaths and rehabilitation during the years of Khruschev’s Thaw and barely any more information in the 1990s, when Gorbatchev’s Perestroika was in full swing. Many of them experienced the loss as a deep personal trauma. The state took away their relatives and posthumously (or for those who were lucky, after decades spent in the Gulag) found them innocent – and, for this, the state can and should be thanked.

The generation of Soviet citizen that experienced Stalinist terror firsthand has taught their children not to ‘get involved’ with the state. State security organs were perceived as particularly terrifying; perhaps, the political stability of the relatively mild Brezhnev’s regime was guaranteed, at least partially, by the submissiveness of citizens who knew from their parents’ firsthand experience that state could commit crimes anytime. No wonder the very thought of charging the state with murder would occur only to the great grandson of the executed – ong after Brezhnev’s death.

Denis Karagodin has brought up the issue of the responsibility of the state and individual perpetrators and – rather than understanding this responsibility in political terms, as has been the case since the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956 – he is talking about criminal responsibility. Indeed, a murder of an innocent person, whoever committed it, requires an investigation that should lead to the punishment of those found guilty. If the criminals were carrying out an order, the whole chain should be punished. Even if nobody involved is still alive, the criminal investigation should name those people and name their acts as a crime.

DEALING WITH THE PAST

Russia has neither a committee on national reconciliation nor a tribunal for those who responsible for state terror. As Alexander Etkind shows in his recent book Warped Mourning, the Gulag is still alive in the Russian society. Its repercussions are felt in culture and science, in personal relations between individuals as well as in the interactions between individuals and the state.

It has been often reiterated that it is utterly impossible to completely condemn Stalinism in Russia because unlike Germany, where denazification was carried out by the occupying powers, the USSR has never suffered military defeat and has to deal with its past on its own. As a result, it is often maintained, the political balance never allowed people to raise the issue of state crimes committed by the Bolsheviks. Stalinist apologists frequently reduce the issue to the total number of victims: are the numbers correct? Aren’t they inflated on purpose? Should we talk about millions of murdered or just about hundreds of thousands? To consider these events as statistics sterilizes them, removing the tragic and criminal elements of the state’s history.

Denis Karagodin suggested his own way to deal with the past: a personal investigation and lawsuit related to the death of his great grandfather. Here, we are not talking about statistics but an individual life. The FSB archives preserve the secrecy of informers and executors – so will they open their secrets upon the request of a citizen?

One may expect that Karagodin’s story will be taken as an example to follow and that other relatives of the executed during the Stalinist terror could file suits. One cannot be certain that the state will comply, but why would they deny such an investigation? Under the Soviet regime, the chief reason was fear; today, to deny a citizen such an investigation, the state has to invent a legally valid answer. This, in turn, may serve as a starting point for a wider public discussion, for this discussion did not happen in the 1950s or late 1980s.

‘BIG HISTORY’ AND FAMILY MEMORY

In the 1980s de-Stalinization was mainly carried out by the media. Many took the form of some kind of propaganda: reporters wrote about repressions, the Memorial Society collected data on the victims while citizens themselves simply ‘consumed’ this information and by a certain point were ‘fed up’ with it – at least, those who did not want to resume any discussions on the Soviet past. Now we are talking about the reconstruction of a family history, and in this very context de-Stalinization may become a personal issue for hundreds of thousands of people.

Some time ago scholars studying historical memory registered a surge of interest in family roots among Russians. Genealogical studies, family history, archival research, search for birth certificates and ancestors’ graves became common for various social strata all over Russia. Instead of the textbook history, Russians more than ever wanted to know about their family’s part in the history of their country. Should there be any unturned pages in the family history, the generation of grandchildren is willing to turn them over.

In the beginning of June, I took part in a scientific conference on historical memory. Among other events, we attended the opening of the exhibition devoted to the conference organizer’s grandfather who served time in GULAG and then lived in exile in Karlag. His grandson found it necessary to reconstruct the tragic and most dramatic events in his grandfather’s life. The webpage of the Memorial Society accumulates more and more information about the victims of Stalin’s purges, and public interest in this webpage is growing. The public movement Last Address installs memorial plaques on the houses from where the victims of state terror left for their deaths. This strong movement for the reconstruction of family histories differs greatly from the struggle to correct interpretation of the previous century’s history, which Soviet intelligentsia discussed in media in the late 1980s. This new memory appears to be more complex and multilayered than any textbook history.

There is an obvious connection between the Karagodin case and the popular movement The Immortal Regiment. In both cases, descendants look at their family history and put it into the context of national history while still looking at this national history from the point of a individual case. In the case of the Immortal Regiment, the state supported this public initiative. Is it ready to support the other one as well? Can citizens change the state?

One would like to believe that there may be positive answers to these questions.

Оригинал

“Назовите имена палачей. Как в России возрождается память о прошлом.” – Иван Курилла (по заказу Иосифа Фурмана – старшего редактора Slon.ru) – 21 июня 2016 – © Slon.ru

Original

Original article in Russian: “Назовите имена палачей. Как в России возрождается память о прошлом“ (Slon.ru) (June 21, 2016) by © Ivan Kurilla – Professor of the Department of Political Science and Sociology, European University at St. Petersburg, Russia; Former Kennan Institute Short-term Scholar; Former Visiting Scholar at The George Washington University Elliott School of International Affairs.

Translation

Translated [July 2016] by © Olga Serebryanaya.

Proofreading [July 2016] by © Ksenia Nouril (Academia.edu Profile).

License

This article may be used freely with credit to © KARAGODIN.ORG [https://karagodin.org/?p=8836]

Последнее обновление: Воскресенье, 17 июля, 2016 в 21:28

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА

Расследование КАРАГОДИНА